Design principles

The purpose of the design principles is same as that of bricks in in the building. That means that as long as quality of bricks is bad, architecture quality won't matter much. Design principles are set of rules applied at the module-level of software. We call them SOLID principles and they are applicable regardless of the paradigm that is used.

These principles are designed to provide:

- Adaptability to changing requirements

- Easily understandable intents

- Reusable components

The acronym SOLID stands for these principles:

- Single responsibility principle

- Open-closed principle

- Liskov substitution principle

- Interface segregation principle

- Dependency inversion principle

todo: we ll try to define them in rest of this article

Single responsibility principle

The name may suggest that this principle is concerned about single responsibility of a module or a function in a way that it should do just one thing, but it's not exactly that.

SRP is described as follows:

A module should have one, and only one reason to change.

So what's the reason why software changes? To satisfy the demands of users and stakeholders. Book defines these as actors and therefore redefines the description:

A module should be responsible to one, and only one actor.

The module usually means a source file, but better definition would be that it's a cohesive set of functions and data structures. Better wording for the purpose of this principle may be:

Gather together the things that change for the same reasons. Separate those things that change for different reasons.

Open-closed principle

The definition of OCP is:

A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification.

This means that requirement extensions should be done by source code extension, not modification. That's not very descriptive, so let's throw some diagrams in here.

The ideal state is that when a new change must be introduced into the code, the amount of existing code that has to be changed should be zero.

Liskov substitution principle

This principle tells us, that every subtype of a given type should be substitutable.

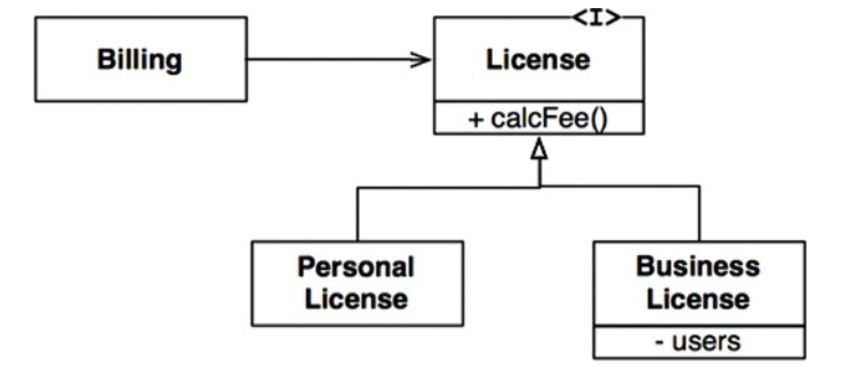

Suppose we have a License type with two derivatives Personal License and Business License. This design conforms the LSP, because both derivatives can be used as License .

Interface segregation principle

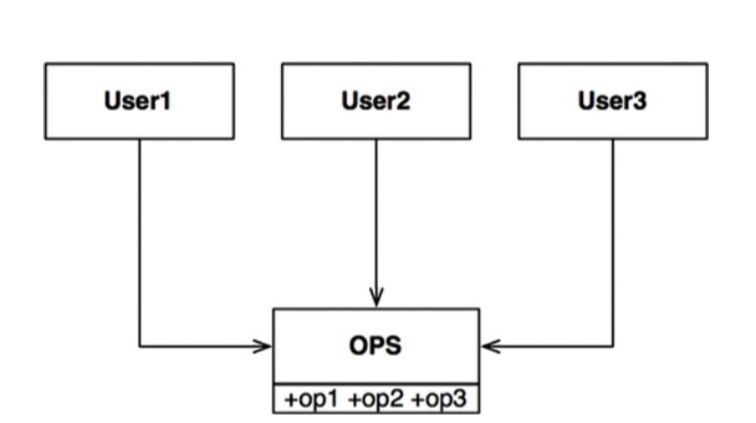

Imagine if we had a class with multiple methods used by multiple dependants, but each dependant only uses one of them:

This can cause all kinds of trouble and is considered harmful, especially in statically typed languages, because changes in one method would force both derivatives to be recompiled when they don't need to.

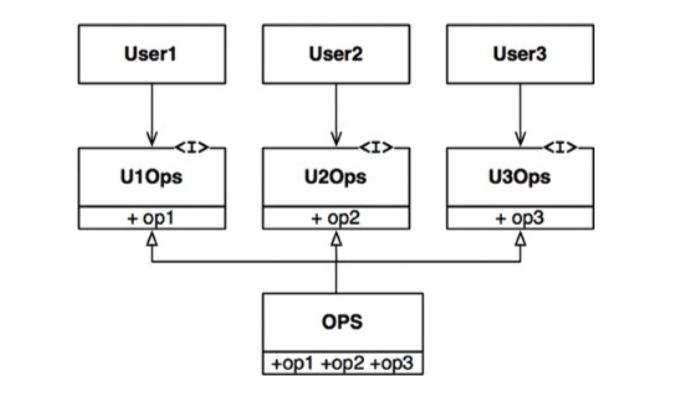

Solution is to segregate this methods into two interfaces and let the dependant use only the method it needs. This solves our problem:

Dependency inversion principle

In previous article we defined what the DI is. It tells us that we need to invert our dependencies, so the changes of their implementation does not affect their dependants which should only be using abstractions (their interfaces).

But there some cases when dependencies don't need to be abstracted away. This violates the DIP, but its main purpose is to abstract away implementations that tend to change.

So what about those, that almost never change? For example the Java String class is quite concrete, but it wouldn't be very beneficial to the codebase to not depend on it. This class is very stable, so the developers don't need to worry about changes made to it.

So the lesson there is that we can comfortably depend on very stable modules, but we should make abstract the ones that tend to change.